Bohemian Garnets

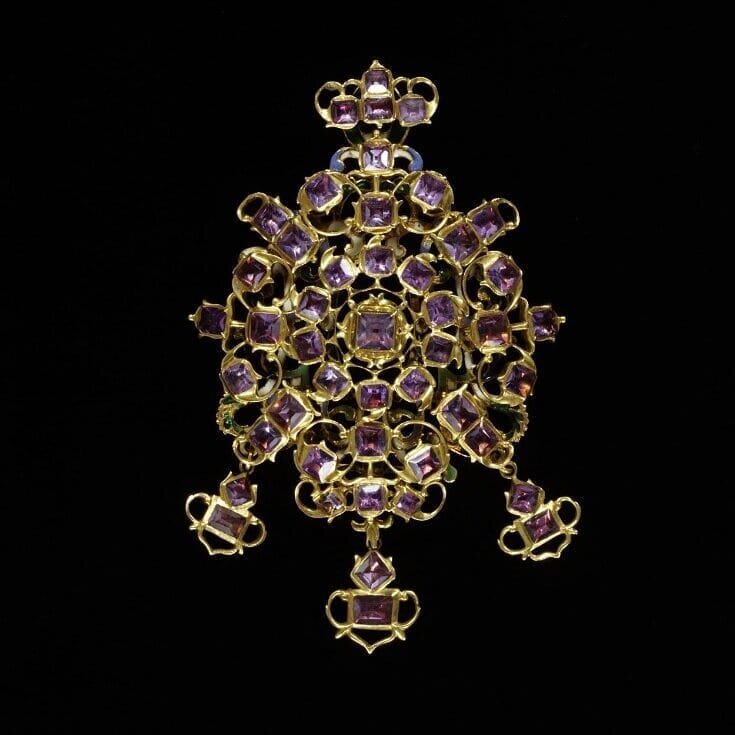

/This Brooch Dates From the Third Quarter of the 19th Century. (Photo Courtesy the National Czech & Slovak Museum & Library)

“Bohemian garnets” are garnets mined in an area once known as Bohemia (it often refers to the entire Czech territory, including Moravia and Czech Silesia). They are the variety of garnet called pyrope (from the Greek words pyr for “fire” and ops for “eye”). Those found in Central Bohemia (in the north of the Czech Republic) are considered to be of the highest quality.

The Bohemian garnet has been mined for over 600 years mostly dug at the mines of Meronitz, and chiefly in the northwestern part of the Czech Republic. The garnets are found in a gravel or conglomerate, resulting from the decomposition of a serpentine. Sometimes, however, they are found in the matrix. When this happens they are often associated with a brown opal. Most of the good quality the stones are small with those as large as approximately 1/4 inch and above being reported rarely. By the 19th century it was determined that the elements creating the intense red color in pyrope were Chromium and Manganese. The color ranges from fiery-red to ruby-red. The Bohemian garnet also possesses excellent clarity, transparency, and has a high refraction of light. This means that the stone has a remarkable sparkle and what has been described as an "inner glow".

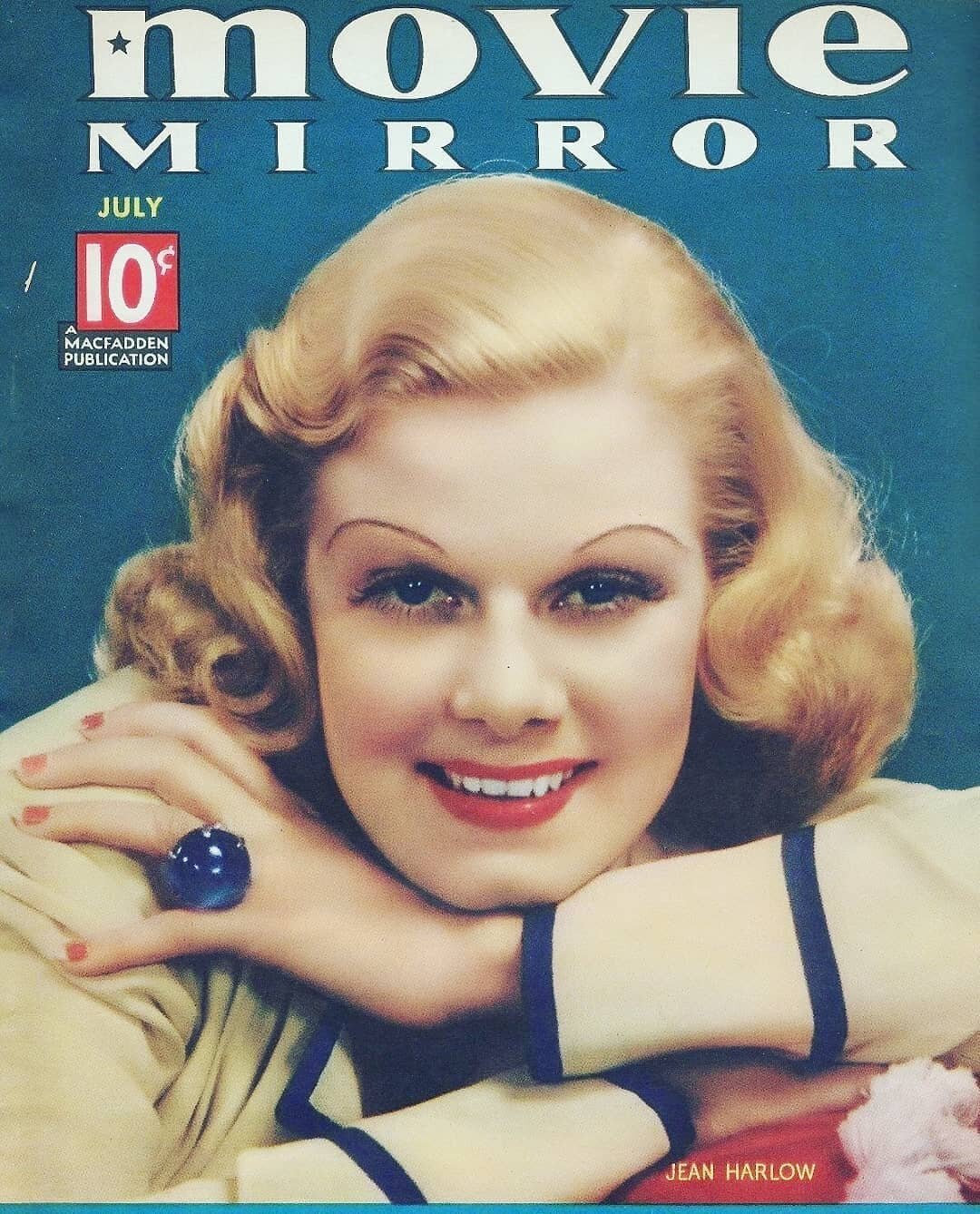

The stone gained popularity in Europe in the 18th and 19th century also becoming a favorite of the Victorians. Traditional Bohemian design placed it's emphasis on the arrangement of the garnets, taking precedence over the metal chosen for a piece of jewelry. George Frederick Kunz cites in his book Rings for the Finger Garnet that rings were generally made of faceted, rose or cabochon cut Garnets in 14 or 18 kt gold. By the late 19th century larger Pyropes were typically brilliant-cut, resulting in very bright (red) stones, whereas the very small stones were usually rose-cut.

This Art Nouveau Style First Appeared in Individual Creations of Designers Rather Than in Industrial Mass Production. (Photo Courtesy The National Czech & Slovak Museum & Library)

An Example of the Mass Produced Items Typical of the Bohemian Garnet. (Photo Courtesy The National Czech & Slovak Museum & Library)

The introduction of larger scale manufacturing of garnet jewelry created mass-produced machine pressed metal settings and garnets of inferior quality. The majority of readily available "Bohemian Garnet" antique jewelry falls into this mass production category. While these pieces are beautiful in their own right, it should be noted that like any piece of jewelry rarity and individuality are valued much more highly.

Antique Pyrope Hairpin From the Smithsonian