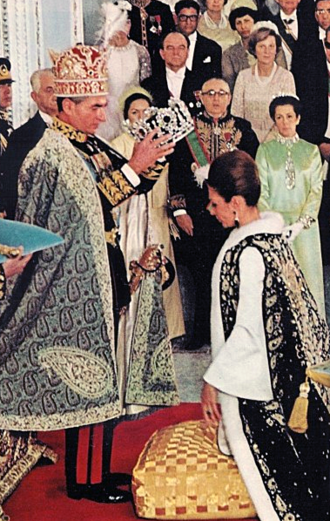

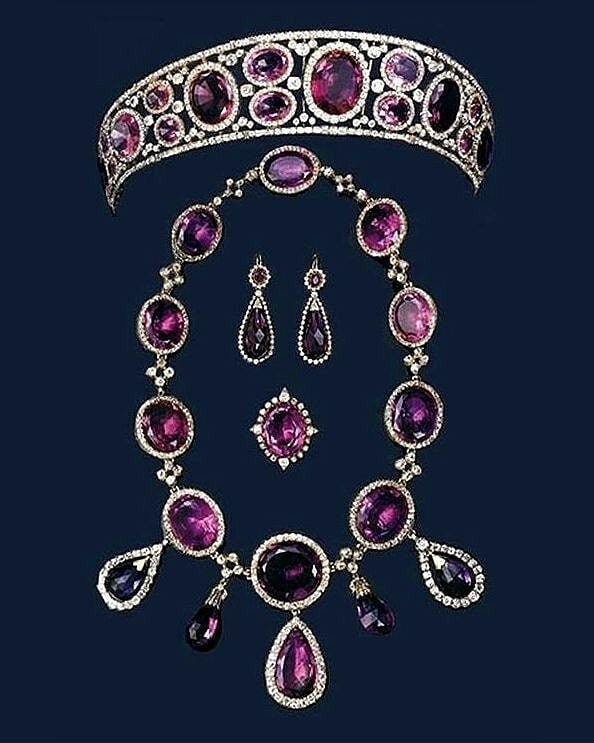

The Crown of Empress Farah Pahlavi

/The Empress Crown: part of the coronation regalia used by the only Empress of Iran, Farah Pahlavi.

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi had already ruled Iran for two decades when he married Farah Dina in 1959, but he not yet had his official coronation. Mohammad Reza Pahlavi put off his coronation saying that he believed he could only be crowned when he truly felt he deserved it. That time came in 1967; the coronation would take place in October of that year and it was set to break with tradition.

For centuries the wives of monarchs were not crowned; only the male ruler had that honor. This changed with Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. In a nod to the White Revolution's mandate on the emancipation of women, Emperor Pahlavi was determined to also have his consort crowned; however, there was a slight problem: since it had been centuries since an Iranian empress had been crowned, there was no appropriate crown available. The honorable task of making the new crown would fall to Van Cleef and Arpels. As was dictated by tradition, the gems used in the crown and coronation jewelry were selected from loose stones already in the Imperial treasury. None of the items that were part of the Imperial treasury were allowed to leave Iran so Van Cleef & Arpels had to send a team of jewelers to Tehran in order to construct the crown. While there, the team, Farah, and other important people in the Iranian government were consulted on the design aspects so that the finished product would be perfect. The crown ended up taking six months to complete.

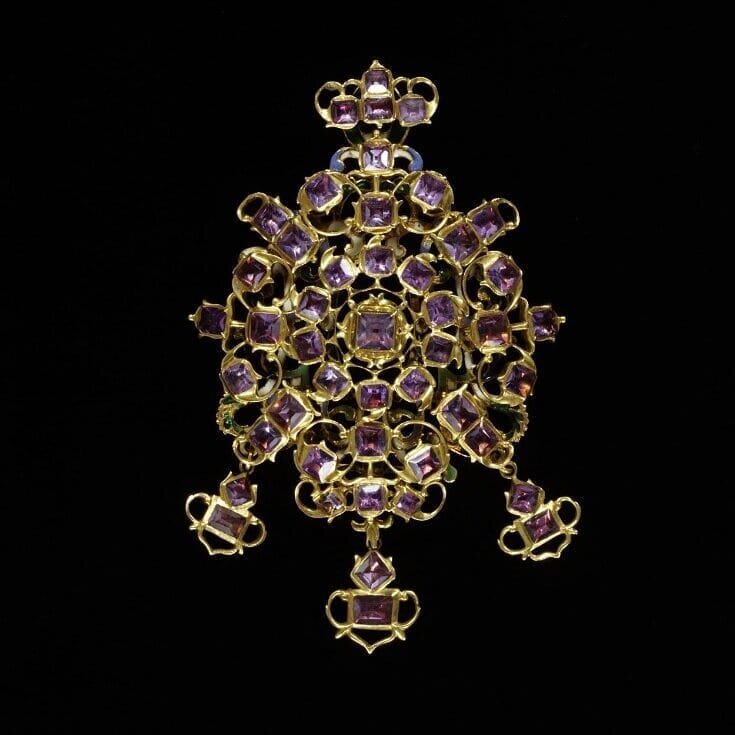

The crown itself is made from white gold and green velvet, covered with diamonds, pearls, emeralds, rubies, and spinels.

By early 1978, the rising discontent in Iran had started to become more evident, eventually leading to demonstrations against the monarchy. The Empress recalled in her memoirs that "there was an increasingly palpable sense of unease". By the year's end riots and political unrest had reached a head and martial law was put into effect. The country was on the verge of open revolution.

On January 16, 1979 both the Emperor and Empress decided to leave the country and begin a life in exile. Empress Farah would be the first and the last Empress to wear the magnificent crown.

When the Iranian revolution occurred it was thought that the Iranian crown jewels might have been lost. Miraculously, most of the collection remained intact and the jewels were put on public display under the presidency of Hashemi Rafsanjani in the 1990s at the Central Bank in Tehran.

To read more about the Empress and her life I suggest checking out her memoir An Enduring Love: My Life with the Shah: A Memoir .